Monday, February 27, 2012

Interesting....

Arnheim says: "If a face is turned sideways, the nose will be perceived as upright in relation to the face but as tilted relative to the entire picture. The artist must see to it not only that the desired effect prevails, but also that the strength of various local frames of reference is clearly proportioned; they must either compensate one another or be subordinated to one another hierarchically. Otherwise the viewer will be confronted with a confusing crossfire" (Arnheim, pg. 101).

-Alison

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Twelve Parts

Blog post 2

Form, Perception, and Unconsciousness

This also makes me think about facial perception. I remember Oliver Sachs mentioning that sometimes patient’s would have a hard time recognizing family and friends because their facialexpression would change. To the patients, the person would look so different that it was hard for them to believe it was the same person. This fact makes me curious about how reliable our vision is—even those with perfect vision. And how this could affect our ability to correctly identify a criminal or the visual details of a crime? Seeing something or someone from a different angle could cause you to believe you are seeing something entirely different. I feel that we often “see”, not with our visual system, but with our brains (previous knowledge and assumptions through past experiences).

Arnheim describes foreshortening in three different ways—1) The image is not orthogonal (as the Egyptian art), 2) The image does not provide a characteristic view of the whole, 3) any image withparts that are changed in proportion or disappear partly or completely. I found the exampleof the “monstrous horse-man” interesting; however, not because I was confused by my knowledge that it was a horse, and my eyes thinking it was a penguin shaped creature. Before I read what Arnheim had to say about it, I was intrigued by the image because I had to study it before I could tell which direction the horse was facing. (I don’t know, maybe that’s just me?) I suppose after reading Arnheim’s description and studying it longer, I am able to better visualize how that image would appear strange or distorted to someone who was not used to seeing objects represented through different perspectives.

As I have never given much thought to form before, I am interested in applying what I am learning to the filmmaking process. Personally, I find the foreshortened and distorted images visually intriguing. I like not immediately knowing what I am looking at, and the process ofpiecing together details to form the image in my mind, which I am consciously or unconsciously basing it from. “The expression conveyed by any visual form is only as clear-cut as the perceptual features that carry it” (Arnheim, pg. 161). This quote has inspired me to experiment with the camera and to tell my story not solely with the images in my film, but with the way the images are shot. I realize that I rely heavily on the image itself and the voices of characters, and I would enjoy making a film that relies almost entirely on the viewer’s interpretation of the images being presented. I am virtually new to everything in the art world, and even filmmaking was something I accidentally stumbled upon last semester. When I made ashort film as my conference project for an oral history course, I put a lot of thought into the story I wanted to share, but not into the aesthetics of the film—because I really had no idea how to make a film. And so I was really surprised by the reaction it got, and my professors seemed tobe shocked that I had no previous experience. It turns out that I did all these things in my film by accident, but now I am wondering if perhaps it wasn’t accidental, but unconscious? And furthermore I wonder how often these unconscious elements appear in artwork? I think that it is great if one does something purposely, but I wouldn’t describe a piece of art as less meaningful or beautiful if it was created without a clear objective in mind. In fact, there is something more artistic about it if it is closely linked to discovery.

Some old and new examples of art and form (foreshortening, overlapping, depth, etc). As well as a bad example of foreshortening!

Distorted Perception

The Real Horse

Later on in the night, the artist tells you she has one more painting waiting at her home. “What is it of?” you ask. That is the assumption: the painting is a duplication of reality, or of something in reality. It’s a “pictorial representation,” as Arnheim puts it. Even if it is a subversion or interpretation of reality, as are Picasso’s drawings (Figures 91a and b), it is still of reality, connected & bound to it, not a painting of its own entity.

Why is so much of Arnheim’s discussion of Form about the representation of an object from real life? Probably & greatly it is a result of the artistic trend throughout history to make art that way. In the Egyptian humans, and the Greek horses, art has been a method of relating to reality, saying something about something real. Even in abstractions, like below in Picasso’s The Guitar Player, titles direct us to the bridge between art and reality. (And if, in these abstract paintings, the title doesn’t give us reality, our cognitive processes do. Arnheim says on page 139, “It makes all the difference whether in an ‘abstract’ painting we see an arrangement of mere shapes...or see instead the organized action of expressive visual forces.” I think the viewer, more often than not, sees an arrangement of shapes; Arnheim assumes a viewer’s choice between the two equally, but I believe there is a tendency to project or infer reality from even the abstracts.)

Why has the representation of reality been the artistic trend? (and where it has not been, why was it the unconscious goal of art viewers?)

Surely there have been painters who have created paintings--self-sufficient entities, detached from reality, images that have nothing to say or do with reality.

It probably isn’t possible. What painter takes brush to canvas without an incentive? a real incentive? A realistic object or objective is what causes the painting. Regarding Figure 102 of Arnheim, we would say that The Silk Beaters is, being a painting, detached from reality--but Hui Tsung was real, and was inspired by real silk-beating women, or the idea of real them, or the objective of making a real statement on real sisterhood. A revolution or viewer’s emotion can be the desired effect of the piece of art. Even in the sudden & unquestioned “surge” an artist might blessedly experience, and then immediately paint without a conscious objective in mind, a painter is real and thus the painting has something to do with reality, by very nature of its irreversible relationship to the painter. It was birthed by something real. Why then, do we talk about a painting as if it is a detached entity?

A tree is real, we would say. A tree is a part of reality. A tree grows; it is not a tree of something, or about anything. It simply is a tree, and none of its existence is devoted to “pictorial representation.”

But is the same tree real if its seeds were planted by a man?

We often perceive (correctly) that what’s in a painting is not limited to the two dimensional plane, but is a three dimensional scene. Our understanding of reality, and objects from reality, leads us to assume and believe the same dimensionality in a painting. Our experience with objects fills in the blanks of Figure 90, from Ballet Mecanique. We assume that outside the frame, this lipsticked woman continues; and that her face is dynamic and three-dimensional, holdable, kissable, and even that it contains a skull and blood. In Salvador Dali’s The Temptation of St. Anthony, in a painting of the non-realistic, even here we process the information in a way that assumes depth and gives shape to objects we’ve never seen in reality. We assume the teetering golden throne is not a cardboard cutout, but a deep and rounded vehicle holding a full woman.

In even more abstract works, we may not see three dimensions. We may not discern anything from reality. But we try, and we would rather have it than not. In Pollock’s Number 14: Gray, we can see different layers of sperm-like swirls, planes on top of planes. We may even assume the dimensionality of the swirls, that they are round and substantial. I think “expressive visual force” is an artistic goal equally valuable than representing reality, but I believe the truth is that viewers look for reality first, and deeply. I know, at least, that I do, very instinctively and not to uphold any conscious “belief.”

Arnheim gives only small value to the role of Knowledge. He says on page 116, “Knowledge may tell us that [Figure 88] is a horse, but contrary perceptual evidence--and should always overrule in the arts--such knowledge, and tells us that this is a penguin shaped creature, a monstrous horse-man.”

At first I found this preposterous: I saw a horse, albeit from a potentially confusing perspective, but a horse from which I could discern the shape of a thing I knew from reality. I knew that at another perspective, I would see the same horse. But after looking at this Greek horse multiple times, I am more likely to see a “monstrous horse-man”-- a two-legged thing with a lumpy, human-sized torso. Maybe this viewing sequence occured because this monster is what I am now looking for, persuaded or directed that way by Arnheim. Maybe I saw a horse originally because I was in such disagreement with Arnheim’s idea that knowledge should be and is overruled, that I looked immediately for the realistic horse.

Regardless of what I see now, I think Arnheim plays down Knowledge too readily. Foreshortenings occur because what is on the painting is not (at least, sometimes is not) the birth of a new thing. It may be a foreshortened perspective of a thing from reality we knew beforehand, with which we compare and fill out the dimensionality of the painted image. Arnheim says on page 117, regarding the foreshortened Mexican man and Greek horse, “It is only our knowledge of what the model object looks like that makes us regard these orthogonal views as deviations from a differently shaped object. The eye does not see it.” But the eye can and often does see it; sometimes it happens after the brain “figures out” that this is a view of a real horse, albeit a bad view, and sometimes the eye sees the horse immediately. And yes, sometimes the horse is not seen, but rather an equine penguin. Looking back now, as I draw my eye up the horse’s legs, telling myself it’s a horse, I see it. This effort is different from the horse I originally & instinctively saw. Maybe Arnheim was right--in both cases, maybe my eye didn’t see a horse at all, at least not without the help of my brain.

But viewing a piece of art is not just done with the eye--the brain obviously is working in conjuction. “The eye does not see it” seems a statement ignorant of the entire cognitive process involved with art perception. Arnheim says that “contrary perceptual evidence overrules,” and thus we should see the horse-monster, taking the visuality of the image as the authority. The image’s percepts are the canon of the image’s story, by which we follow information. This is what’s on the Greek vase; this is what is. It may be easier for you to wrap your head around a horse from reality, but this isn’t reality, this is art; this is a vase.

The word in Arnheim’s statement, “should,” is the important word. Arnheim believes that justly--rightly, even morally--the viewer of the art must abide by the perceptual evidence, and disregard the temptation of Knowledge. Knowledge, he and I both believe, makes it easier to “see” an image, to understand what it is of and what is occurring. But that application of knowledge assigns information to the art that isn’t true, because it’s not what is in the art! It’s only the projection of reality onto the art, by the viewer. And while I agree with Arnheim on that that, what should happen is not necessarily what happens. Knowledge makes an image easier to understand. As long as artists continue to leave holes in paintings, the viewers will continue to fill them with reality.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

What Is Art?

Is it possible to create art without meaning?

There have been many occasions where I’ve sat down and surrounded myself with a wide variety of tools to create art. I will have my watercolor pencils, my oil pastels, charcoal, graphite, pen and ink. But, all I see when I look down in front of me is a large, blank, white sheet of paper. For me, inspiration can be difficult to express. I feel the influence of my surroundings, but getting it on paper takes work. And what exactly is inspiration? It’s an idea pulled from something else. Is there always a message connected to inspiration? Is there a message in all art that is created? Certainly all art has meaning, right?

If one was to create a piece solely for the intention of making something beautiful or aesthetically pleasing, lacking any meaning, can we call it art? Perhaps creations that are produced for appearance alone can only be called decorations rather than art. Yet, Arnheim said that, “Every painting or sculpture carries meaning. Whether representational or ‘abstract’, it is ‘about something’; it is a statement about the nature of our experience.” We are all touched in some way by the images we see. Creating something just for beauty’s sake must involve some range of emotion. All emotions have meaning to them, so in a sense, the ‘piece without meaning’ actually has meaning.

Arnheim goes on to say, “Compositions by adults are rarely as simple as the conceptions of children; when they are, we tend to doubt the maturity of the maker. This is so because the human brain is the most complex mechanism in nature, and when a person fashions a statement that is to be worthy of him, he must make it rich enough to reflect the richness of his mind.” I agree that logically, of course the ideas presented in an adult’s artwork will be more complex than that of a child’s. But, that doesn’t mean that a piece of art that is presented simply or stylistically child-like should be looked down upon. It is important to see the value in the simplicity of a child’s work. Children see the world so simply and purely – while their artwork may lack the depth of an adult’s, there are certainly ideas present that, as adults, we may forget over time because our perception of our world has changed. Yet, most children may not have any intention in sending a message or presenting an idea. But, that’s the beauty of art – it can be ambiguous.

I’m not completely sure how I feel about Arnheim’s rules for balance and shape in art. I mean, I understand his ideas and I agree with most of what he says, but to me, art is a form of expression. Approaching art should not be a serious thing. It is there, naturally, for everyone. I think techniques are important to create an aesthetically pleasing art piece, but I also think it sort of takes away from the purity or freedom of art, itself. When I sit down to an empty sheet of paper with a strong desire to express my thoughts and emotions, I am not interested in following guidelines for how to make a balanced work. It is an intuitive process. (Actually, everything I’m saying is causing me to second guess myself because I do agree with a lot of Arnheim’s statements, I just didn’t like how I felt about them while I was reading. I need to think about it more. Or maybe create more art.)

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Balance, imagination and Pina Bausch

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Two-dimensional Movement

Sunday, February 12, 2012

the Phantasms of Colours

"by what modes or actions Light produceth in our minds the Phantasms of Colours is not so easie"

Like Issac Newton, I've found that understanding color and our perceptions of it to be quite daunting. So much so that I was afraid I was colorblind or had some sort of malfunctioning rods or cones at the beginning of this class! I have been involved in art all my life but have struggled in understanding the world of color. The readings, though, have shed much light on the subject and I hope my rational mind will be able to catch up with my visual perceptions. I was struck by the fact that though many cultures define the range of colors to be continuous in the color wheel, there is actually physically no "continuity between the longest-wavelength red light that we can see and the shortest-wavelength blue" (Livingstone 85). I was also fascinated by Livingstone's discussion of how color creates edges by means of surround antagonism (92). The visual system can give different responses to different wavelengths of light is interesting to note insofar as it enables the visual system to have another way to distinguish objects in addition to shape and luminance (95). This is interesting in the different sources of light we encounter -- daylight, tungsten and fluorescent. We don't normally notice the differences in these lights but if our color-selective cells did not have a surround organization, out perception of an object's color would vary dramatically. Its interesting that the ability to see a color is dependant on the surrounding ones. Though our visual system is adept to not recognize the color of the illuminant, the lighting conditions can dramatically alter a color's value.

I was also intrigued by Livingstone's discussion of peripheral vision is fascinating in how the mind will assume shapes and objects that are only hinted at, such as seen in many impressionist paintings. This phenomenon, illusory conjunction, has really stuck with me as I go through the visual world. I wonder how this effects our perceptions both positively and negatively throughout our daily lives. This brings me to Mamassian's article, which discussed the ambiguity of visual art:

"Visual perception is ambiguous and visual arts play with these ambiguities. Ambiguities in visual perception are resolved thanks to prior constraints that are often derived from the knowledge of statistics of natural scenes. Ambiguities in visual arts are resolved thanks to conventions that found their inspirations from perceptual priors or, more interestingly, from other sources such as stylistic or arbitrary choices" (2152).

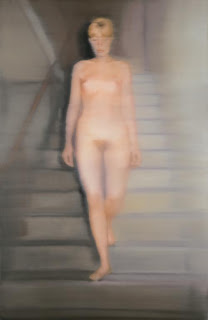

The ambiguity in art is something I am very intrigued by and attracted to. Most of my favorite works are very ambiguous in nature. I grew up with a love of the Impressionists and am currently obsessed with the blurry nature of oil paintings and photographs such as those of Gerhard Richter. The ability of artistic mediums to portray movement and utilize the visual system's amazing abilities to import information from suggested colors and shapes is fascinating. I will conclude with a few of Richter's works and would like to explore further the use of ambiguity in our psychological perceptions.